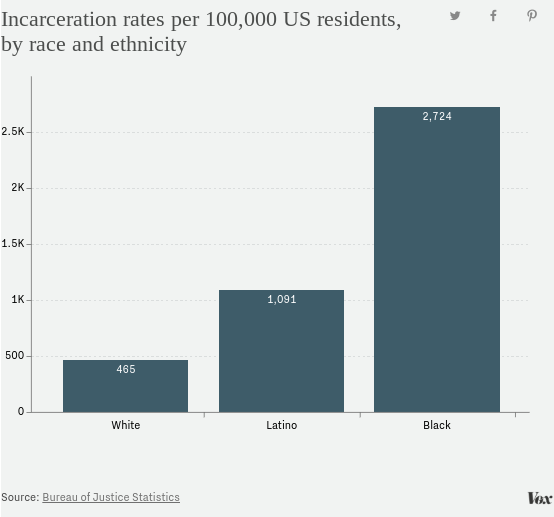

According to NAP, in 1972, 161 per 100,000 of the US population was incarcerated. However, at the end of 2016, this number had risen to 655 for every 100,000. This means that currently around 2.2 million adults are behind the bars in US prisons and jails. As seen in the bar chart below, it has been claimed that the War on Drugs started in 1971 has disproportionately harmed black and African American communities, particularly black men.(Vox) One of the ways this has happened is through the stop-and-frisk interrogations used by the police to find drug-users and traffickers on the streets. A NYCLU study has shown that between 2002-2017, black people are around 55% of all stop-and-frisk targets of the NYPD, while whites constitute between 9-15% of such targets. This data clearly shows systemic discrimination against black and African-American communities since according to the 2010 census, 33% of NYC population was white, and 26% was black. (furmancenter.org) As a result, black men are almost 6 times as likely to be incarcerated as white men. (Vox) So, if systemic discrimination has been the reason for the disproportionate targeting of black men, why hasn’t Title VI been effective to prevent minority groups from being incarcerated?

Title VI of 1964 “prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color or national origin in any program or activity that receives Federal funds or other Federal financial assistance.” (hhs.gov) More specifically, this law claims to prevent “a predominantly minority community…[being] subjected to harsher rules than a predominantly non-minority community.” Even though Title VI is supposed to protect minority groups from discriminatory treatment from federally funded institutions like the police department, the law is highly inaccessible in the case of stop-and-frisk operations.

First, the methods based on direct evidence can rarely be used to prove that racial discrimination has happened in the age of political correctness. The method(s) of direct evidence consists of either “express” classifications or “comments or conduct by decision-makers as direct evidence of intent.” (justice.gov) When charged with racial bias in a case of stop-and-frisk, it is very unlikely that a police officer will admit to have interrogated someone based solely on their racial background. Moreover, most states allow the police to stop and interrogate anyone on the street based on their judgement of reasonable suspicion, and anything can constitute reasonable suspicion, including but not limited to suspect “was wearing low-waisted jeans,” or “looked nervous”, or even “didn’t look nervous.” This allows the police to always have a justification if they get charged with a Title VI violation. Once the charge has been dismissed, the prosecution can take place as normal, and lead to conviction of the person targeted in the stop-and-frisk.

While Title VI violations can easily be ignored and covered in individual instances of stop-and-frisk, Title VI also protects minority groups from “systemic or widespread discrimination.” (justice.gov) According to the US Department of Justice, “one means of proving intentional discrimination is through circumstantial evidence showing a statistical disparity that affects a large number of individuals.” In the case of stop-and-frisk, one could show how police departments tend to systematically target poor African-American neighborhoods over rich, white, suburban or college neighborhoods, which have almost identical chances of having possession of illegal drugs and marijuana. However, reasonable suspicion can be used to justify frisking African-American neighborhoods: the police can effortlessly claim that drug-related activities and crimes have been found to happen in similar neighborhoods. This tactic of reasonable suspicion has been and continues to be used to justify the targeting of black men in stop-and-frisk operations.

Stop-and-frisk operations are unfair and harmful since it gives government institutions like the police immense power to target specific groups and individuals. At the end of the day, each person has prejudices and biases and controlling such variables would be incredibly difficult. A person committing the same crime should not be penalized more than another based on the color of their skin and socio-economic background. In America, black people are thrown under the bus frequently. As long as the police are allowed to conduct stop-and-frisk operations in the neighborhoods that they choose, the enforcement of Title VI to protect black and African-American men from statistically unfair rates of incarceration is next to impossible.