We all remember the watch parties, the calm before the storm, watching the blue states turn red, and suddenly the results were in. They were not as expected, nor as projected. The results of the 2016 presidential election were jarring for some–especially media moguls–and people frantically searched for a reason as to why democracy had failed them, and they found one: the polls. While the polls did generally predict that Hillary would win, were the polls drastically off the mark, or were Americans simply looking for any reason beyond themselves, that Mr. Trump had been elected as POTUS? Unfortunately for some, the latter is most certainly true.

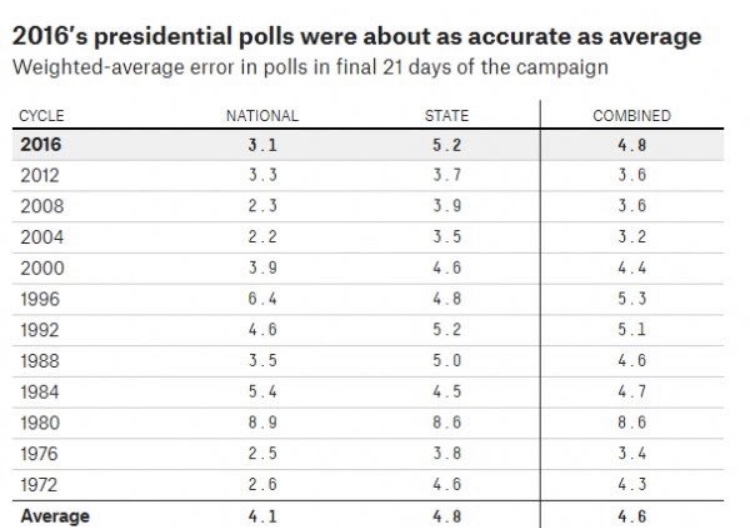

The above graph shows the margin of error of voting in the polls between two candidates of that respective election cycle. Meaning that the polls missed the actual voting margin of Trump and Clinton in 2016 by 3.1 percent–a full point below the national average error in polling (the total average at the bottom of the chart). Per the graph, polls done in the 2004, 2008, and 2012 election were all highly accurate and potentially gave false expectations to those who depended on polls for trending data concerning what was happening throughout the 2016 election, but the results above show that the 2016 polls fared more accurate than the national historical average, and were no reason to sound the alarm.

The accuracy of the polls is further explained in a 2017 report by the American Association for Public Opinion Research, which confirms that the polls were not to blame.

“National polls were among the most accurate in estimating the popular vote since 1936. Collectively, they indicated that Clinton had about a 3 percentage point lead, and they were basically correct; she ultimately won the popular vote by 2 percentage points”.

(Kennedy, et al.)

Although Clinton did secure the popular vote, further polling showed that the electoral college vote was where the upset occurred.

“Eight states with more than a third of the electoral votes needed to win the presidency had polls showing a lead of three points or less (Trende 2016)”.

(Kennedy, et al.)

The RealClearPolitics poll Trende pulled from noted that Clinton had a narrow projected electoral college victory (272-266) and Trump only needed to win a single battle-ground state (one of the eight mentioned in the quote above) to secure the election. Trump’s win notably came from winning in Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin (all of which were predictably ‘blue states’ prior to the 2016 election) and while the polls were not 100% correct, they were not statistically significant in their margin of error such that Americans could blame the polls for giving them the false hope of having their first female, democratic president.

Although the polls were not remarkably erroneous, there are obvious critiques as to how polling could be improved. From the 2016 election, polling cites did not expect Trump’s overwhelming support in the Midwest, or the Shy Trump Effect (where voters claimed to be a Clinton supporter, but voted for Trump come election day), and a plethora of other variables. Polling can, and most certainly should be, improved to produce better results in the future. However, despite all the uncontrollable variables, the 2016 polls were not to blame for the election results and they were not unreliable. Inevitably, 2016 was a volatile race that was statistically too close to call, but the polls did a pretty damn good job of trying.

All we can do is hope for a better 2020, and let the polls keep polling.

Resources:

Kennedy, Courtney, et al. “An Evaluation of 2016 Election Polls in the U.S.” AAPOR, American Association for Public Opinion Research, http://www.aapor.org/Education-Resources/Reports/An-Evaluation-of-2016-Election-Polls-in-the-U-S.aspx.

Gelman, Andrew, and Julia Azari. “19 Things We Learned from the 2016 Election.” Taylor and Francis Online, Journal of Statistics and Public Policy, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2330443X.2017.1356775.