Over the past decade gun violence has amplified in frequency, press coverage, and egregious outcomes in the United States. The news has been filled with stories about mass shootings- Sandy Hook, Aurora, Orlando, Sutherland Spring, Las Vegas, Parkland, Thousand Oaks, Squirrel Hill, and many more. There are even more stories about gun-related suicide deaths, gun-related homicide with in the home, and gun-related injuries. Still it can be difficult to disentangle the misinformation and lack of understand that surrounds the gun violence epidemic. One reason this issue exists is because of the difficulty the United States Government, specifically the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, has had gathering data on gun violence. In this blog post I will look at the CDC in an attempt to understand ways we can improve our understanding of the gun violence epidemic.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention is a federal agency that researches the health, preparation, and prevention in the United States to create national strategies to improve public wellbeing. Many people think about the CDC in terms of the diseases and conditions it studies, but the CDC also conducts research on motor vehicle injuries, prescription drug overdoses, child abuse, sexual violence, and more. Unfortunately, for years the CDC was unable to advocate for gun control as a result of the Dicky Amendment. This amendment was created in response to a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine that concluded gun ownership was a risk factor for homicide in the home. The amendment allowed the CDC to study gun violence, but took a away the vast majority of funding for that research. Although many of these restriction were removed from the CDC in 2018, I believe that the Dickey Amendment was and continues to be a significant contributing factor to the misinformation and lack of understanding that surrounds gun violence.

What’s worse still is that the information the CDC can provide about the gun violence may be fundamentally flawed. First, the CDC is only recording the number of gun-related injuries and deaths in 40 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico in their NVDRS database, which means that a little over 19% of the country is unaccounted for. It’s difficult to gain a pervasive understanding of gun-related injuries and deaths in the United States when 19% of the data that should be gathered is missing.

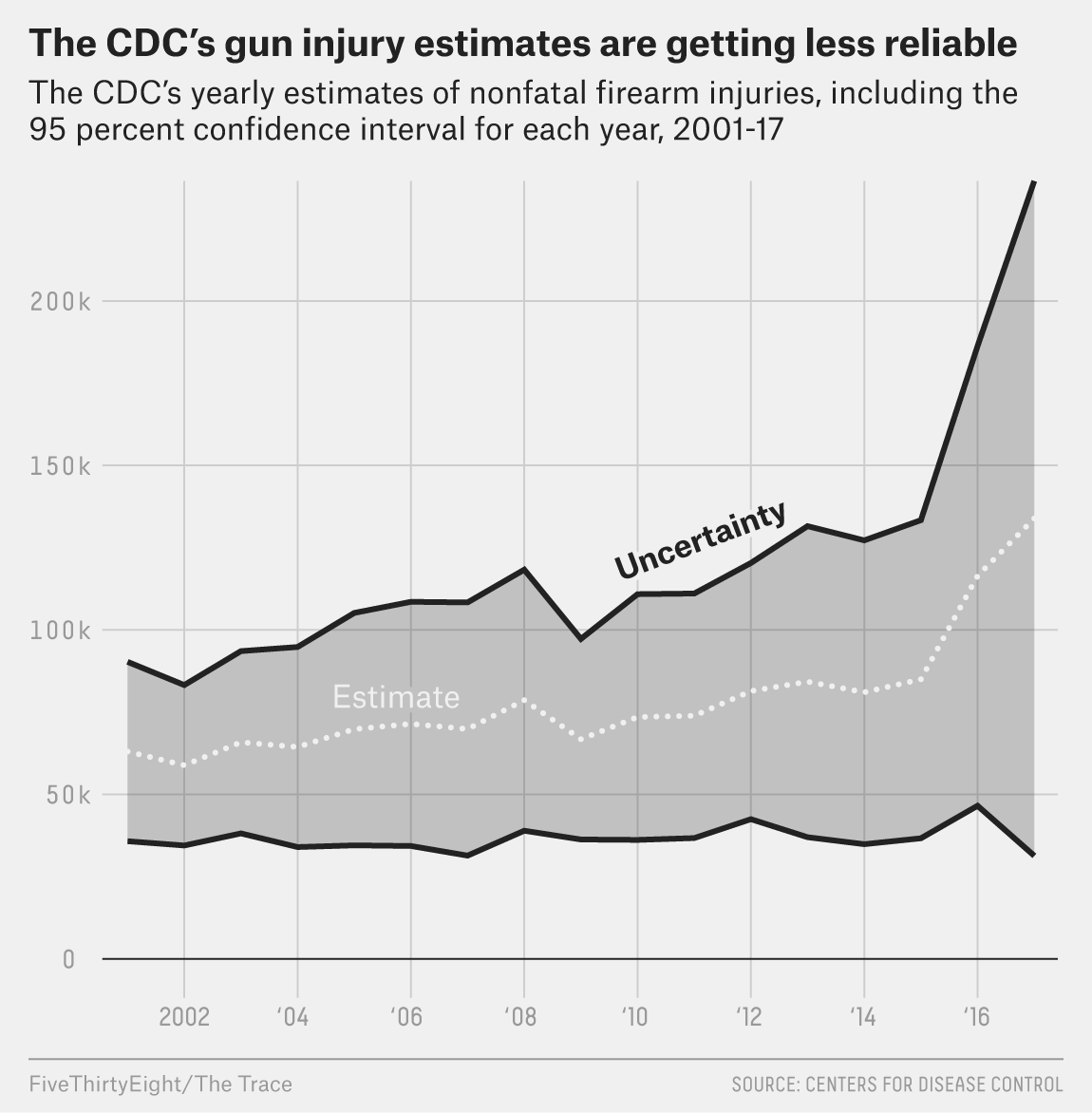

As a result of increasing funding restrictions, the CDC had been decreasing their sampling pool. In 2017 the CDC only gathered data from 66 hospitals according to a meta-analysis conducted by FiveThirtyEight and the Trace. A sampling pool that small has the potential to drastically skew a dataset. What if one hospital treats more gun wounds than is standard? Or less? How are we supposed to determine a standard for the country based off of 60 hospitals? This is reflected in the data reported from 2017. That year the CDC reported that somewhere between 31,000 and 236,000 people were injured by guns, which is four times wider then what they reported in 2001.

The graph above highlights the level of uncertainty from the coefficient of variation (a measurement of the standard error) from 2001 to 2017. The coefficient variable rose from 22.1 percent to 39.1 percent over that time. According to the CDC a national estimate should be considered unstable and potentially unreliable if the coefficient variable exceeds 30 percent, so 39.1 seems to reflect the precariousness and failing of the CDC’s sampling.

The impact of this unreliable reporting from the CDC is far-reaching. The data collected by the CDC is used by researchers, journalists, reporters, professors, and lawmakers. There is a lot of opportunity for that data to be warped before it reaches the general public. As a country we need to obtain a better understanding of the gun violence epidemic we face, and we can not do that without reliable data to guide our political actions.

References:

About CDC 24-7 | About | CDC. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/about/default.htmCameron, C. (2018, March 20). Gun Violence:

Cameron, C. (2018, March 20). Gun Violence: Why the CDC Doesn’t Study It. https://www.healthline.com/health-news/why-cdc-isnt-studying-gun-violence#10

Kellermann, Arthur L., et al. “Gun ownership as a risk factor for homicide in the home.” New England Journal of Medicine329.15 (1993): 1084-1091.

Campbell, S., & Nass, D. (2019, March 29). 11 Senators Want To Know Why The CDC’s Gun Injury Estimates Are Unreliable. Retrieved from https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/11-senators-want-to-know-why-the-cdcs-gun-injury-estimates-are-unreliable/

The CDC’s Gun Injury Data Is Becoming Even More Unreliable. (2019, March 11). Retrieved from https://www.thetrace.org/2019/03/cdc-nonfatal-gun-injuries-update/

Campbell, S., Nass, D., & Nguyen, M. (2018, October 04). The CDC Is Publishing Unreliable Data On Gun Injuries. People Are Using It Anyway. Retrieved from https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-cdc-is-publishing-unreliable-data-on-gun-injuries-people-are-using-it-anyway/

Definitions for Nonfatal Injury Reports | Nonfatal Injury Reports Help Menu | WISQARS | Injury Center | CDC. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/nonfatal_help/definitions_nonfatal.html#advancedstatistics