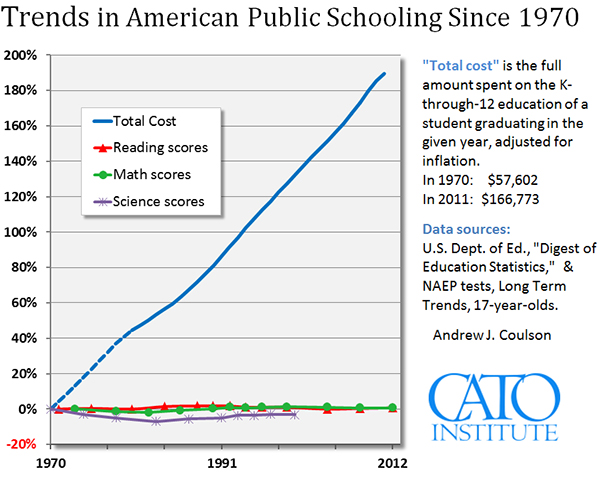

The Digital Age has undoubtedly broadened the accessibility of information, and the American education system has begun to evolve accordingly. The Heritage Foundation announced that “online learning is revolutionizing K-12 education and benefiting students” (Lips, 2010, p. 1). The same publication describes that “[a]s many as 1 million children (roughly 2 percent of the K-12 student population) are participating in some form of online learning” (Lips, 2010, p. 1) and cites a meta-analysis from the U.S. Department of Education that found that “students who took all or part of their class online performed better, on average, than those taking the same course through traditional face-to-face instruction” (U.S. Department of Education, 2010, p. xiv). The Heritage Foundation article repeatedly mentions online learning’s potential to reduce taxes because of its lower cost compared to funding educators. However, by advocating for this cheaper alternative to traditional methods of education, the Heritage Foundation supports the reduction of professional opportunities for women in the education sector.

Despite making up the majority of the field, women are disproportionately underrepresented in schools’ administrative positions.. While 76% of public and private K-12 teachers are female (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Schools and Staffing Survey, 2012c), women hold only 51.6% of principal positions at public schools (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Schools and Staffing Survey, 2012b) and 55.4% at private ones (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Schools and Staffing Survey, 2012a). When it comes to salary, a study in Pennsylvania found pay gaps between male and female K-12 educators that “actually grow” (Barnum, 2018, para. 6) when controlling for outside factors such as the teacher’s education level and experience. Therefore, not only do women complete most of the work in the education profession, they are undervalued as represented by their underrepresentation in more prestigious positions and unfair remuneration.

Because the majority of K-12 educators are female, the online learning movement, which seeks to replace educators with technology and software, reduces professional opportunities for women. This report from the Heritage Foundation promotes online learning by emphasizing its low cost; specifically, the author cites Terry M. Moe and John E. Chubb’s Liberating Learning, where the authors “estimate that a school could reduce its teaching staff by approximately one-sixth if elementary school students spent one our per day learning electronically” (Lips, 2010, p. 5). Ideologically, replacing educators with digital systems represents a lack of respect for teaching as a profession, and this movement paints teaching as formulaic and mechanical.

The Heritage Foundation advocates for replacing teaching staff, of whom the majority are women and facing a gender pay gap, with online learning systems. This notion continues to resist the view of teaching as a profession and, if enacted, would mainly disadvantage women instead of men in the sector, who are more likely to hold more powerful positions.

References

Barnum, M. (2018). Chalkbeat. In female-dominated education field, women still lag behind in pay, according to two new studies. Retrieved from https://chalkbeat.org/posts/us/2018/06/15/in-female-dominated-education-field-women-still-lag-behind-in-pay-according-to-two-new-studies/

Lips, D. (2010). The Heritage Foundation. How online learning is revolutionizing K-12 education and benefiting students. Retrieved from https://www.heritage.org/technology/report/how-online-learning-revolutionizing-k-12-education-and-benefiting-students#_ftn5

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Schools and Staffing Survey. (2012). Average and median age of private school principals, and percentage distribution of principals, by age category, sex, and affiliation: 2011-2012. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/sass/tables/sass1112_2013313_p2a_002.asp

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Schools and Staffing Survey. (2012). Number and percentage distribution of public school principals by gender, race, and selected principal characteristics: 2011-2012. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/sass/tables/sass1112_490_a1n.asp

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Schools and Staffing Survey. (2012). Total number of select public and private school teachers and percentage distribution of select public and private school teachers, by age category, sex, and selected main teaching assignment: 2011-2012. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/sass/tables/sass1112_20170221001_t12n.asp

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning Evaluation, and Policy Development. (2010). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/tech/evidence-based-practices/finalreport.pdf