In 2012, more than 50% of Americans owned a smartphone and teen depression rates have drastically been on the rise since 2011. Unsurprisingly, multiple studies have focused on the “iGen” (those born between 1995 and 2012–per Twenge, 2017) and followed the trends of increased screen time and teenage depression rates. Jean Twenge explains in her article “Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?” that there is a stark positive correlation between these two variables. It would seem, then, that to decrease teens’ likelihood of experiencing depression, they should also decrease their screen time. Unfortunately, the solution to alleviating teen depression is far more complex than simply turning off their cell phones, and Twenge creates causations from her data that are most likely just correlations and patterns that need a more in-depth analysis.

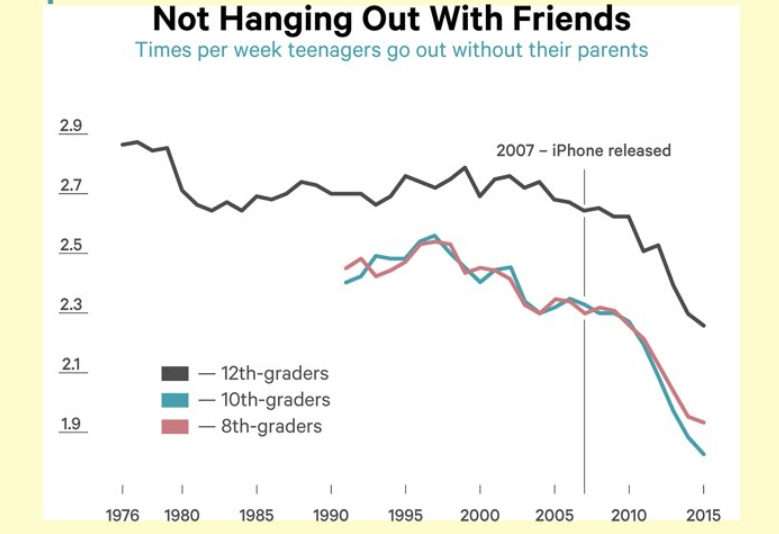

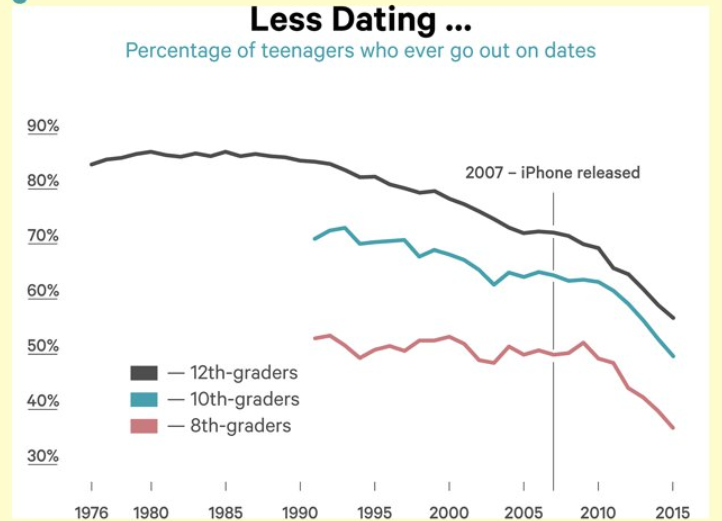

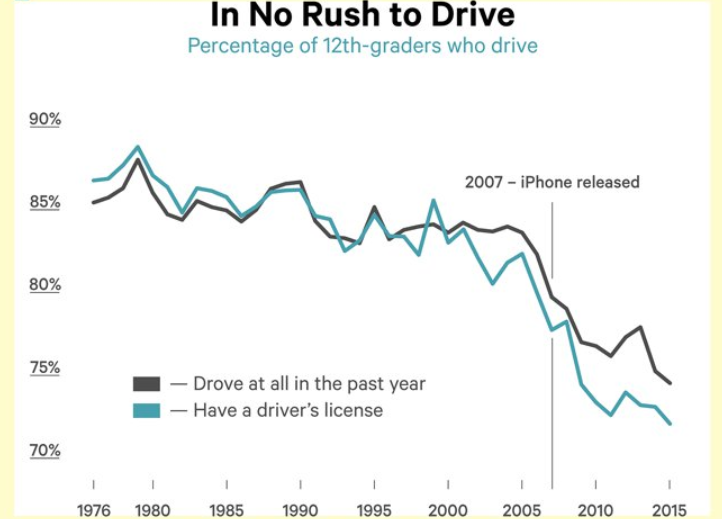

Twenge draws connections between screen time and teen depression by noting the three following trends (also depicted in the graphs above): “12th-graders in 2015 were going out less often than eighth-graders did as recently as 2009″, “..only about 56 percent of high-school seniors in 2015 went out on dates; for Boomers and Gen Xers, the number was about 85 percent” and that one in four teens lack a drivers license by the time they finish high school (Twenge, 2017). Essentially, teens today are single, staying home, aren’t driving anywhere, and are horridly depressed. Although the statistics provided are interesting, they do not analyze the crux of the problem, and merely hope that the numbers will provide a valid-enough argument to make the case that phone time leads to depressive teens. The overarching conclusion is that “Teens who spend three hours a day or more on electronic devices are 35 percent more likely to have a risk factor for suicide, such as making a suicide plan” (Twenge, 2017) and further categorizes risk factors into gender and age groups. Although this data shows relevant trends that need to be addressed, unfortunately analysts like Twenge are chasing parked cars and spewing data that is already well-known, without delving into the real issue.

Brian Resnick of Vox addresses the lack of conclusive evidence of studies linking tech use and teen depression, by reminding readers that the data right now is inconclusive and warrants further inquiry, but not a doomsday narrative.

“Studies like these are rife with such caveats, and more. In general, such studies do not asses causality, they do not include clinical assessments of mental health (just questionnaires), they somewhat arbitrarily define what counts as well-being, they rely on self-reports, and they often use “screen time” or “electronic device use” as a catchall variable to include any type of media use”.

Resnick, 2019

One problem with the question of teen depression and screen time, is in the question itself. What is screen time? Researches like Twenge use ‘screen time’ as an overarching variable that encompasses: reading, writing, studying, social media, etc. which is a complex variable that needs to be delineated to draw a more direct conclusion. There are also not plausible, effective methods for monitoring screen time without a breach of privacy or accounting for frequent user-reported errors such as reporting that they spent time reading news instead of scrolling through Facebook.

Finally, defining a subjective variable such as depression is incredibly difficult and can alter results based on the definition. In the Twenge study, suicidal factors were determined by whether participants ‘felt depressed for more than two days in a row over a two week time period’ instead of reported suicide attempts, for example.

The correlation between screen time and teen depression is a question that is more than worthy of significant inquiry. However, we must also question what and who is on the screen that is making such a negative impact on our youth population, instead of demonizing the smartphone industry and screen time as a whole. For now, the data needs more work and teens (and the general population) should be aware of factors within their screen time that may induce negative feelings.

Resources:

Twenge, Jean M. “Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 19 Mar. 2018, http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/09/has-the-smartphone-destroyed-a-generation/534198/.

Resnick, Brian. “Have Smartphones Really Destroyed a Generation? We Don’t Know.” Vox, Vox, 22 Feb. 2019, http://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2019/2/20/18210498/smartphones-tech-social-media-teens-depression-anxiety-research.