Recently I’ve found myself becoming more and more interested in how to conduct non-biased, objective research. My interest stems from my academic and career goals to conduct research one day. While I consider honesty of very high importance especially in research, I also realize that even the most honest researcher can fall victim to their very own cognitive biases. Unconscious influences can result in self-deception which in turn affects how even the best scientist analyzes his or her data. This is important because misinterpreted data can result in long-term consequences for the representative scientific community. In the article How Scientists Fool Themselves – and How They Can Stop Regina Nuzzo discusses cognitive biases that can have an impact on the analysis of data. She opens the article by telling the story of Andrew Gelman, a statistician who had a wrong sign on one of his variables, but because the results seemed reasonable he didn’t go back through his data and check it. He published his work and some years later when a graduate student discovered the error, Gelman had to publish a correction stating that the findings were essentially wrong. There’s no way of knowing how many people read his original study and never saw the correction. This just goes to show how important producing objective research is because once data is out there for all to see you can’t really erase it. With it being so easy for the brain to fool researchers how can biases be reduced to preserve objectivity and publish reliable data?

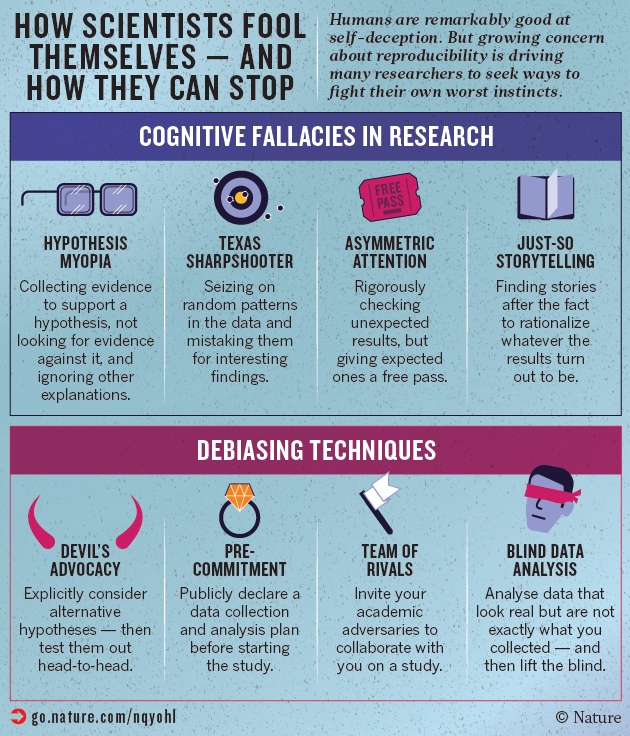

The first part of a solution to this problem is to acknowledge that no one is exempt from cognitive bias and to understand what biases are at play when analyzing data. According to Nuzzo, there are four biases that can cause one to misconstrue the results of research. Hypothesis myopia is when researchers become so focused on supporting their hypothesis by collecting evidence that they fail to consider refuting the evidence and alternative explanations. I think the issue with this is fairly clear. When we fail to consider other explanations we create one-sided stories that could be proliferated and have the potential to affect the literature of a topic. Nuzzo explains that the next bias is, “illustrated by the fable of the Texas sharpshooter: an inept marksman who fires a random pattern of bullets at the side of a barn draws a target around the biggest clump of bullet holes, and points proudly at his success.” This cognitive bias causes researchers to ignore the big picture and focus on the “most agreeable and interesting” results. Examples of this bias at play happen in p-hacking (exploiting degrees of freedom until p<0.5 is reached) and something called HARKing (Hypothesizing After the Results are Known). The next bias is asymmetric attention to detail or disconfirmation bias. As seen in the case of Andrew Gelman, this bias happens when non-expected results are scrupulously checked over, but “reasonable” results receive little scrutiny. It surprises me to find out how common this is. According to Nuzzo:

“In 2011, an analysis of over 250 psychology papers found that more than 1 in 10 of the p-values was incorrect— and that when the errors were big enough to change the statistical significance of the result, more than 90% of the mistakes were in favour of the researchers’ expectations, making a non-significant finding significant.”

This really goes to show how often this occurs and how important it is to overcome this bias. Last, but not least is just-so storytelling. This is when researchers construct a narrative to rationalize their results after the results are obtained. As Nuzzo explains, the issue with this is that a researcher can use these stories to support “anything and everything” when used in this way.

As stated by Nuzzo each bias represents a trap in which the science of identifying salient relationships is accelerated. She states that the key to avoiding these traps is to “slow down, be skeptical of findings and eliminate false positives and dead ends”, in essence, use the brakes. As the image below shows, the article poses a wide variety of techniques that a researcher can use to prevent these fallacies from interfering with how researchers look at data. Using a technique called strong interference in which researchers develop experiments to rule out alternative hypotheses and explanations, can combat hypothesis myopia. In order to do this one must first gather alternative explanations. In my eyes looking at competing hypotheses is a no-brainer and any thorough researcher would do this, however, with our brains looking for easy answers it’s easy to see how this still continues to occur. The next solution presented in the article is transparency and open science. Researchers have a lot of leeway when it comes to analyzing and presenting their findings. This method encourages researchers to share all of their methods, data, computer code and results so that others can analyze and confirm research findings. This ensures that what a researcher finds really conveys what the data indicates. Another way of collaborating with others to avoid bias is by working with researchers that hold opposing views. According to the article when talking about this, Daniel Kahneman states, “You need to assume you’re not going to change anyone’s mind completely, but you can turn that into an interesting argument and intelligent conversation that people can listen to and evaluate.” This technique seems like it could be the most useful technique mentioned in the article. Hypothetically the competing researchers would cancel out or reduce the effect of hypothesis myopia, asymmetric attention, and just so-storytelling. The final comment on how to avoid bias consists of using a program to produce alternative data sets which are all analyzed alongside the real data in a process called blind data analysis. The actual results are not revealed until the researcher completes the analysis. This method appears as one of the best methods because researchers are blind to the actual data so they have no way of knowing if the data is significant or not during analysis. In doing this biases are kept at bay and objectivity remains intact.

Insight into these fallacies offers a glimpse into the many biases people use to make decisions. These biases in research have the potential to distort the information available to scientists which informs future research and scientific debates. Learning about these fallacies not only gives me real-world examples of how cognitive biases could one day affect my work but what I can do to overcome them. I can’t stress enough about the importance of applying these techniques in my research so that it is not only objective and transparent, but reproducible. While we can’t get rid of the inherent bias we carry with us, these methods offer a good start to ease the damage they can cause to research, scientific data, and a researchers reputation.

“Science is an ongoing race between our inventing ways to fool ourselves, and our inventing ways to avoid fooling ourselves.”

Saul Perlmutter, astrophysicist at the University of California, Berkeley

References Nuzzo, Regina. “How Scientists Fool Themselves – and How They Can Stop.” Nature, vol. 526, no. 7572, 2015, pp. 182–185., doi:10.1038/526182a.