Participatory Politics is defined as “Interactive, peer-based acts through which individuals seek to exert influence on issues of public concern”. Data from the Participatory Politics Study by New Media and Youth Political Action suggests that 41% of young people ages 15-24 engage in participatory politics, most of which is in the social media realm.

(Cohen & Kahne YPP Study)

Donald Trump and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez may be political opposites, but they share one major trait in common: their knowledge and influence over social media platforms which encourage participatory politics. Facebook comment wars are commonplace, Instagram and Twitter have become legitimate sources of information for millennials and younger generations, and participatory politics is growing in popularity and scope. However, when analyzing the increasing trend of participatory politics, it is important to analyze the minority level of engagement so that political figures may accurately spread information that can be seen/heard by their intended audience. So, does the increase in participatory politics accurately represent the minority youth?

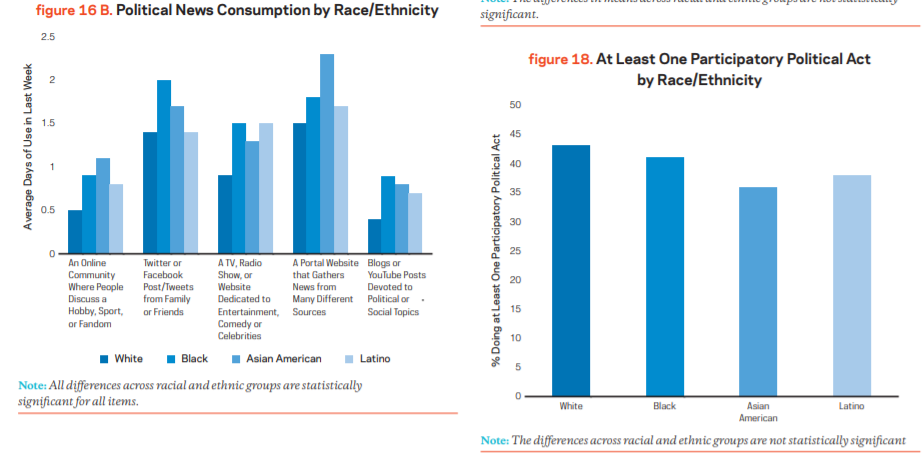

Cathy J. Cohen of the University of Chicago and Joseph Kahne of Mills College (along with their respective research teams) conducted a survey with 3,000 participants aged 15-25 years old. Their participant base included “large numbers of Black, Latino, and Asian-American respondents” (Cohen & Kahne 9) from a variety of states and socio-economic backgrounds. The diversity of this data-set is promising and draws from minority groups to be more representative, so Cohen and Kahne drew the following graphical conclusions from their survey:

Figure 16 B shows that the general youth currently gather their information from participatory channels such as Twitter and Facebook as well as interpersonal relationships, instead of traditional forms of media such as newspaper and magazines. Furthermore, the disparity between races and their average participatory actions within a week, is significantly less than most would assume—as seen in figure 18 on the right. The four surveyed races have a similar percentage of participatory political acts, and visit/interact with multiple channels of information gathering; meaning that activity in participatory politics is racially diverse according to this specific sample.

The conclusions drawn from the sample are sound, however the sample is not entirely representative. Cohen and Kahne admit that “Because the sampling design deviated from a simple random sample of the population, particularly in its oversampling of minority groups, the raw data are not a representative sample of young people in the US” (Cohen & Kahne 40). However, a priority of the study was to include more minority youth, so the claim that it is not a simple random sample is true, but it should not detract from the validity of the study. If anything, this study should be expanded upon to include more minority races, and gather more respondents to continue to legitimize the sample and its conclusions.

From Cohen and Kahne’s study, it is apparent that the racial differences within participatory politics do exist, but the differences are not as large as one may have previously thought. It is important to recognize the racial and socio-economic limitations of minority groups so that others can help to bridge the divide, and create a more cohesive society that is politically informed and has equal opportunity to exercise their privilege to participate in political issues.

References:

Cohen, Cathy J, and Joseph Kahne. Participatory Politics. MacArthur Foundation’s Digital Media and Learning Initiative, ypp.dmlcentral.net/sites/all/files/publications/YPP_Survey_Report_FULL.pdf.