Beginning in April, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral arguments concerning the legality of the Trump administration adding a citizenship question to the 2020 census. The reasoning that the Department of Justice gives for the addition is that to be able to efficiently enforce Section two of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits voting discrimination based on race or membership in a minority group (Lind, 2019). Opponents to the question argue that this addition will discourage millions of immigrants living in the U.S. from filling out the survey, and will threaten the integrity of the data set. What are the potential problems with underrepresentation in the U.S. census count?

The U.S. constitution requires a count of all people people within the U.S. every ten years (art. 1, sec. 2). This has been interpreted to include all people, regardless of citizenship status. This count is used to determine representation in congress, designation of voting districts and allocation of funds. Every ten years, the government goes through the task of trying to count every human being residing within the United States. This is an enormous undertaking that requires public cooperation. In 2010, only 72% of Americans responded with the forms by mail (Lind, 2019). Temporary census takers were hired to fill in the rest of the gaps, but renters, people experiencing homelessness, and topographically complex areas made the process much more difficult, census takers in some cases having to visit houses up to six times. Estimates are around 95% accuracy (Lind, 2019). However, because low-income and minority populations tend to have more transient housing situations, these are the communities in which undercounting more often occurs.

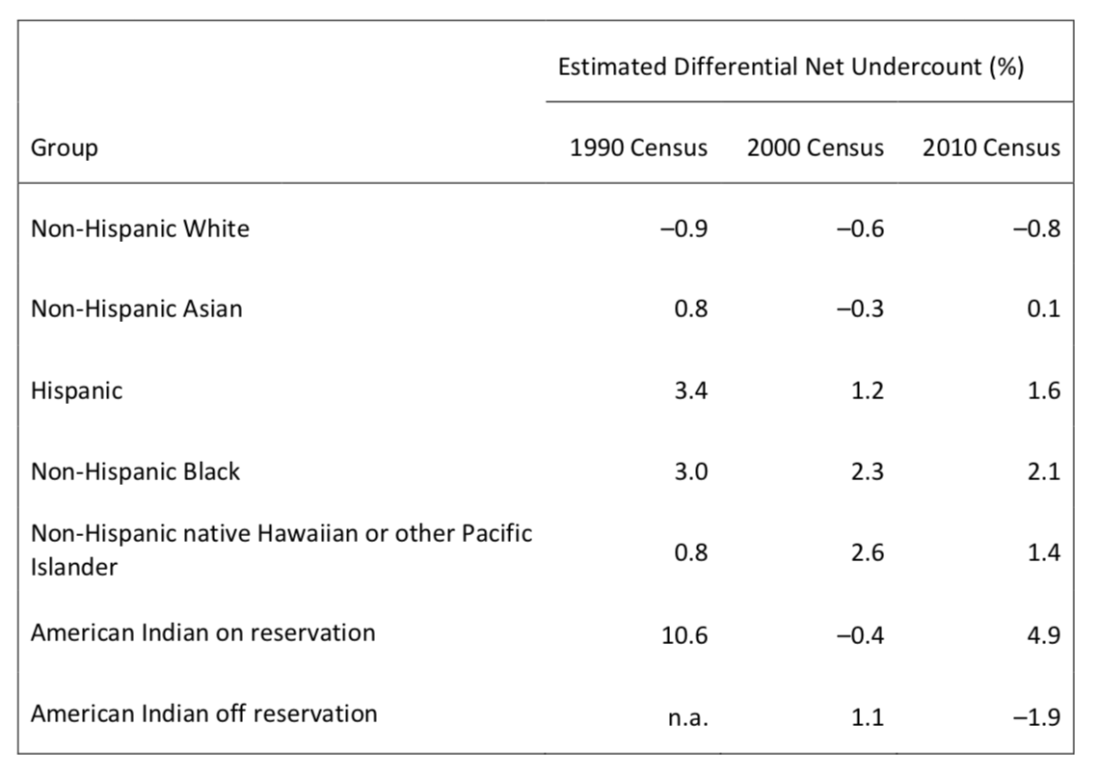

Table 1. Estimated differential net undercount rates for demographic groups in last 3 censuses.

H. Hogan, P. J. Cantwell, J. Devine, V. T. Mule Jr, V. Velkoff, Quality and the 2010 census. Popul. Res. Policy. Rev. 32, 637–662 (2013).

The above chart shows estimations of undercounting in the past three censuses. With the current census questionnaire, it is estimated that Latino populations were undercounted by 1.2 percent in 2000 and 1.5 percent in 2010. Although the Census Bureau says that this change was not statistically significant, with the growing Latino population, this proportion will continue to grow larger. The 2010 census had an average measured error of 0.6% for states. If the same error holds true for the 2020 census, researchers project that Texas loses and Minnesota gains a seat. If the error increases to 0.7% Florida will lose a seat, and Ohio will gain a seat. If the error increases to 1.7%, Texas will lose a second seat, and it will go to Rhode Island (Seeskin, 2018). These changes are not the result of demographic shifts, but from errors in data. States with high minority populations face the impacts of these errors. Less representation means that their specific needs hold less priority in governmental decisions, and the areas that they live in receive receive a smaller proportion of allocated funds.

This is all before the addition of the citizenship question. The worry is that the census could pass along citizenship data to immigration authorities, which could lead to deportation. Although the Census Bureau cannot legally share individual’s information with other branches of government, the current administration’s policies on immigration and citizenship do not breed confidence. Opponents predict that many people without citizenship status, and even immigrants with citizenship would be less inclined to fill out the form if they have to answer a citizenship question. As of 2016, nearly 44 million immigrants lived in the U.S., making about about 13.5% of the total population (Zong, et al, 2018). If this huge proportion of the population is not accounted for in the census, it will result in significant changes in allocation of resources, with mainly low-income and minority populations affected. It should also be noted that this is the first time that congress is using a cost target instead of an accuracy target, which brings into question how committed this administration is to getting an accurate count.

References

H. Hogan, P. J. Cantwell, J. Devine, V. T. Mule Jr, V. Velkoff, Quality and the 2010 census. Popul. Res. Policy. Rev. 32, 637–662 (2013).

Lind, Dara. “The Census Lawsuit Headed Straight to the Supreme Court, Explained.” Vox.com, Vox Media Inc., 15 Feb. 2019, http://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2019/2/15/18226578/census-supreme-court-lawsuit-citizenship-question.

Seeskin, Zachary. “Balancing 2020 Census Cost and Accuracy: Consequences for Congressional Apportionment and Fund Allocations.” Northwestern Institute for Policy Research, 11 May 2018, www.ipr.northwestern.edu/publications/docs/workingpapers/2018/wp-18-10.pdf.

Zong, Jie, et al. “Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States.” Migrationpolicy.org, 27 Feb. 2018, http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states.