In 2016, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) published a monumental study examining the measurable academic effects of increased school funding. Using individual student scores (instead of combined data from entire schools) on the National Assessment of Educational Progress exam, the researchers found that funding-increasing reforms “lead to sharp, immediate, and sustained increases in spending in low-income school districts [and] increases in the achievement of students in these districts, phasing in gradually over the years following the reform” (Lafortune, Rothstein, & Whitmore Schanzenbach, 2016).

The researchers contextualize their study in the “so-called ‘adequacy’ era,” referring to the shift in many states’ funding strategies following the Kentucky Supreme Court Case Rose v. Council for Better Education (1989). The case yielded requirements to adequately fund education in order for the state to fulfill the Kentucky Constitution’s provision for “an efficient system of common schools” (Education Law Center, n.d.). The decision prompted similarly equitable changes to the funding formulas for several other states’ K-12 public education systems (Education Law Center, n.d.). Because of this partial shift in funding ideologies, the researchers use it as the marker of the “equal funding” mindset’s transition into the current “adequate funding” one.

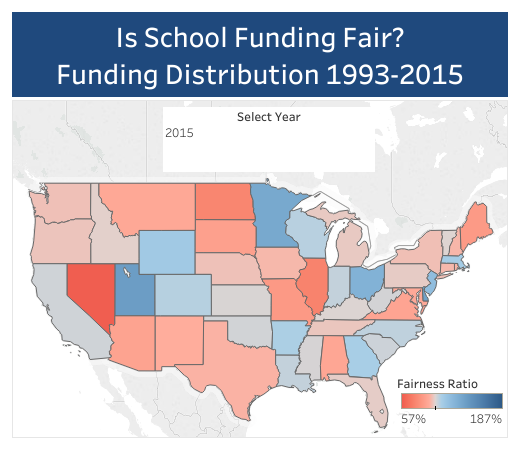

Despite Lafortune, Rothstein, and Whitmore Schanzenbach’s findings, a nationwide study from the Education Law Center and Rutgers Graduate School of Education on school funding by district poverty level concluded that “[t]he majority of states have unfair funding systems… that ignore the need for additional funding in high-poverty districts” (Baker, Farrie, & Sciarra, 2018, p. iv). The photo below is from an interactive map and shows data from the same study. The reality of education funding aligns with the model included in former President George W. Bush’ No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. In the speech he delivered before officially authorizing the legislation, he announced, “we’re going to spend more money, more resources, but they’ll be directed at methods that work. Not feel-good methods, not sound-good methods, but methods that actually work” (Strauss, 2015). The NBER found increased funding to be effective, but Bush based success on standardized test results, which are statistically and unjustly correlated with students’ socioeconomic statuses (Marcus, 2017). Considering this, it is unsurprising that Bush did not consider equitable funding to districts with high proportions of low-income students a “feel-good method.”

While it is important that researchers like these from the NBER publicize data-backed studies promoting equity in school funding, the disconnect between scholarship and practice is alarming. From a social justice standpoint, the education system’s fundamental role in students’ life trajectories makes it responsible for interrupting social reproduction, which describes the upper class’ persistent generational transference of wealth without more equal redistribution in society. Despite findings such as the NBER’s, Baker, Farrie, and Sciarra (2018) demonstrate that most states ignore the proven possibility of equal outcomes between districts and the ability of increased funding to combat outside social-political factors that low-income students face; these states’ decisions perpetuate social reproduction via the education system by failing to interrupt disparities between districts.

References

Baker, B. D., Farrie, D., & Sciarra, D. (2018). Is school funding fair? A national report card (7th ed.). Education Law Center & Rutgers Graduate School of Education. Retrieved from http://www.schoolfundingfairness.org/is-school-funding-fair/reports

Carey, K., & Harris, E. A. (2016, December 12). It turns out spending more probably does improve education. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/12/nyregion/it-turns-out-spending-more-probably-does-improve-education.html

Education Law Center. (n.d.) State profile: Kentucky. Retrieved from http://www.edlawcenter.org/states/kentucky.html

Lafortune, J., Rothstein, J., & Whitmore Schanzenbach, D. (2016). School finance reform and the distribution of student achievement. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10(2), 1-26. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w22011

Marcus, J. (2017, August 16). The newest advantage of being rich in America? Higher grades. The Hechinger Report. Retrieved from https://hechingerreport.org/newest-advantage-rich-america-higher-grades/

Strauss, V. (2015, December 9). Why it’s worth re-reading George W. Bush’s 2002 No Child Left Behind speech. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2015/12/09/why-its-worth-re-reading-george-w-bushs-2002-no-child-left-behind-speech/?utm_term=.15bc027b16a7