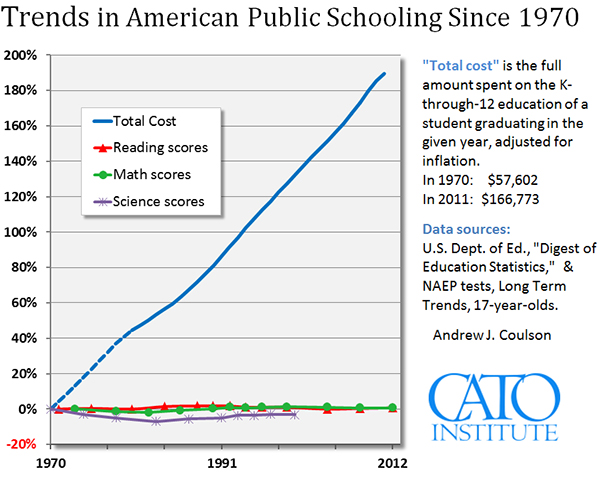

In recent decades, the American public education system has seen a rise in demands for school choice and privatization. These movements work within a larger shift towards neoliberalism in education. Major proponents of school choice capitalize on parents’ desire to send their children to the seemingly best school; to sell their own schools, they antagonize the public education system in an effort to convince parents to support legislation that would allow the transference of tax dollars from public schools to these stakeholders. In their introductory article on school choice, the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom supports this movement and (irresponsibly) uses data on federal education spending and test scores to paint a misleading picture of the American public education system.

The article displays the above graph to portray federal education spending as wasteful and ineffective. However, the authors fail to consider the plethora of resources that public schools are now expected to provide. Since 1980, districts have increased spending on Title I schools (those with large low-income populations), technology, English language acquisition programs, special education, career and technical education, and assessments (U.S. Department of Education, 2018). These changes and increases in spending reflect a changing social context and student population. For example, in the past almost fifty years, the country’s percentage of people who speak English as a second language has grown (Ravitch, 2014). Considering schools’ growing role as an institution of language acquisition, it is remarkable (and attributable to increased funding) that they have achieved approximately the same scores on the long-term NAEP exam.

Additionally, it is unfounded for the authors to assess schools’ effectiveness or quality on test scores, and this graph in particular misconstrues their meaning. By demonstrating the 90% increase in total cost, the Cato Institute implies that a 90% increase in test scores would be satisfactory. This is unreasonable considering that the average seventeen-year-old’s long-term NAEP score in 1970 was 285 out of 500 — if the score were to match the budget’s increase, it would rise to 541. Not only is this higher than what is possible on the exam, but a perfect score on the exam is itself ridiculous because the long-term NAEP test scores on a scale of accuracy, not proficiency. A perfect score on the long-term NAEP exam does not indicate being at “grade level” or subject proficiency.

The Cato Institute portrays assessment data as reflective of the education system’s quality and links school funding to the expectation of increased “success” on these exams. However, this view of the public education system lacks nuance and regard for the growing role that schools play in youth’s lives. Instead, depending on assessment data for a depiction of schools’ effectiveness disregards the resources that these institutions provide.

References

Cato Institute. Educational freedom: An introduction. Retrieved from https://www.cato.org/education-wiki/educational-freedom-an-introduction

National Center for Education Statistics (2013). The Nation’s Report Card: Trends in academic progress 2012 (NCES 2013-456). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, Washington, D.C. See Digest of Education Statistics 2013, table 221.85. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/pdf/coe_cnj.pdf

Ravitch, D. (2014). Reign of error: The hoax of the privatization movement and the danger to America’s public schools. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

U.S. Department of Education. (2018). Education department budget history table (1980 – 2019). Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/budget/history/edhistory.pdf