The tumultuous 2016 election was the beginning of never-before-seen political volatility that has left both sides of the isle questioning the future of the American people and the country. Over 800,000 federal employees plead for compromise as the government shutdown enters its fifth week, so why are their concerns falling on deaf ears?

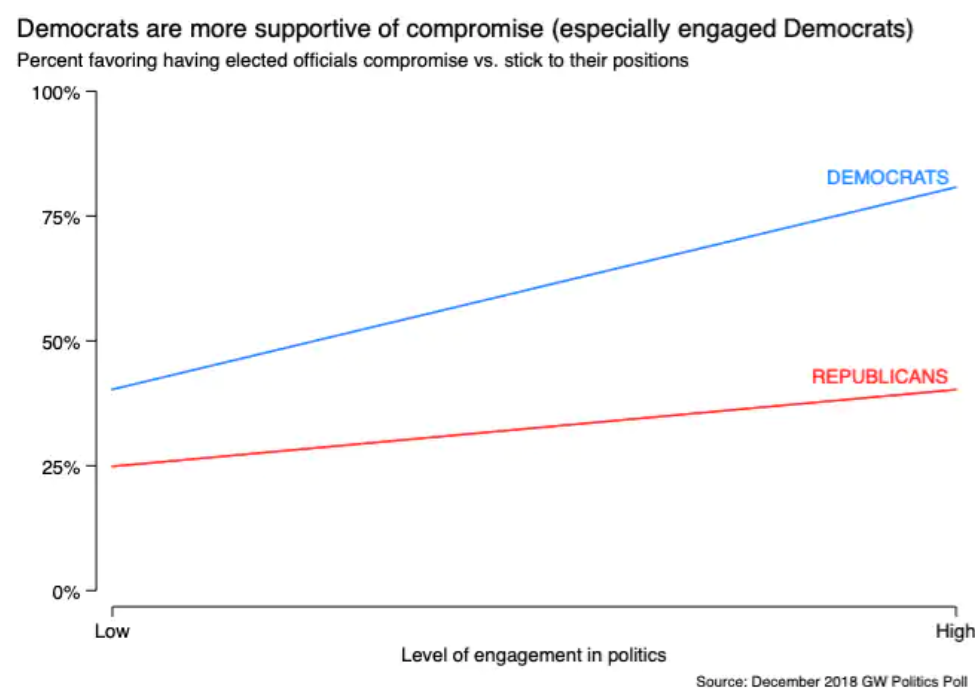

John Sides from the Washington Post provides the graph below which shows that politically engaged Democrats are more apt for compromise than their Republican counterparts. This data can be applied to the government shutdown fairly easily: House Democrats are eager for a compromise, but the Republican president refuses any proposal that does not satisfy his requirements, leading to a prolonged shutdown. Unfortunately, the data within the graph is not that simple and the conclusion drawn by John Sides is problematic. We must examine the terminology of the data to understand why the conclusion that Democrats favor compromise more so than Republicans is fallacious.

The first flaw with Slides’ conclusion stems from the source of the data which determines the meaning of “political engagement”. The GW Politics Poll is cited in a book by John Zaller, who cites his own “comprehensive theory to explain how people acquire political information from the mass media and convert it into political preferences” (Zaller2011). Novels upon novels have been written about the influence of media within politics, and determining one’s political engagement based on mass media consumption is obviously problematic for a plethora of reasons.

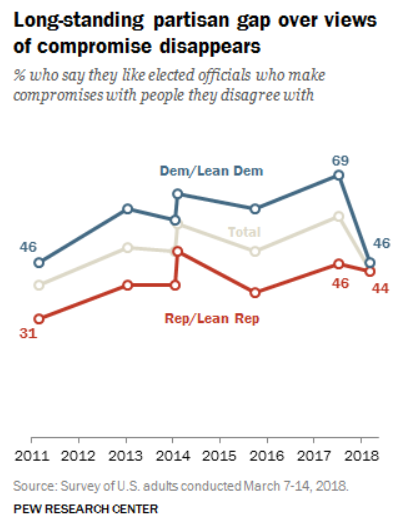

Slides further confuses the reader by affirming that politically engaged people are also synonymous with those who are more educated—cited with data from the Pew Research center. If one were to look at the same webpage as where Slides found data on the educational gap for compromise, you would see that Pew has determined that the political gap for compromises does not exist as shown in the second graph below.

Slides has selected data that pertains to his argument that Democrats are more willing to compromise, while ignoring data from a source he pulled from in the same article. Despite this obvious dilemma of sources and validity between Slides and Pew Research Center, neither source defines nor scales “compromise”. For arguments sake, it is highly difficult (if not impossible) to argue the existence or nonexistence of compromise when one has not defined what compromise is or looks like.

Although Slides attempted to explain the government shutdown through his own lense, the conflicting terminology of politically engaged/educated and lack of definition for compromise create a muddy conclusion that is difficult to discern the truthfulness of the data. If a reader did not click the links Slides provided in the article to discover Pew’s opposing research, their opinion could be based on improper data. As we all have learned, there is more to a graph than what is shown, and this instance is no different. Franklin D. Roosevelt summarizes it best with the quote: “In politics, nothing happens by accident. If it happens, you can bet it was planned that way”.

Sources:

Sides, John. “Many Americans Say They Want Politicians to Compromise. But Maybe They Don’t.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 16 Jan. 2019, www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2019/01/16/many-americans-say-they- want-politicians-to-compromise-but-maybe-they dont/?utm_term=.fb111d5b7f36.

“8. The Tone of Political Debate, Compromise with Political Opponents.” Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 18 Sept. 2018, www.people-press.org/2018/04/26/8-the-tone-of-political-debate-compromise- with-political- opponents/.

Zaller, John R. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge University Press, 2011.